LOW-CARBON, HIGH-PERFORMANCE SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURE IN TORONTO

Stone’s Throw Design provides sustainable architecture in Toronto that lowers carbon emissions, enhances occupant comfort, and boosts long-term building performance.

SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURE IN TORONTO

Sustainable architecture is where art meets ethics in the built environment. It’s a design approach that reduces the environmental footprint of construction by prioritizing natural materials, smart design strategies, and long-term performance.

We look closely at every material—its embodied energy, where it’s sourced, and whether it truly supports the goals of a responsible, future-focused project. But sustainability doesn’t stop at construction. It also asks: How will this building perform for decades to come?

From Toronto to Muskoka and across Ontario, the following design strategies help us create comfortable, resilient, low-energy buildings that tread lightly on the planet.

Sustainable architecture delivers the best results when performance is addressed early in the design process.

Passive Solar Design

Passive solar design is one of the most effective—and often most affordable—ways to reduce a building’s energy use. By thoughtfully capturing the sun’s natural heat and daylight, we can significantly reduce mechanical heating and artificial lighting without compromising comfort.

When combined with high-performance insulation, strategic thermal mass, and well-insulated, energy-efficient windows, passive solar design helps create stable indoor temperatures year-round. A home oriented toward the sun feels naturally warm and inviting; it’s a powerful renewable resource hiding in plain sight. Much like plants turn toward the light, our buildings can do the same, gaining efficiency with minimal additional cost.

Through detailed energy modelling, we can fine-tune the ratio of window area to wall area, ensuring spaces are bright and warm without risking overheating. Even on challenging sites with limited southern exposure, thoughtful three-dimensional design can still capture essential solar gains. Triple-glazed windows then seal in that comfort, maintaining a balanced, cozy environment in every season.

Thermal Envelope

A building’s thermal envelope is the continuous, insulated boundary that separates the indoor environment from the outdoors. It includes the exterior walls, roof, floor, windows, and doors—essentially the entire protective shell of your home. When all these components are insulated to the right levels and connected without gaps, the result is a comfortable, stable indoor environment that requires very little heating or cooling.

Think of the thermal envelope as both a winter coat and a summer umbrella. It shields you from increasingly intense weather while performing several functions at once: it forms part of the structure, keeps out wind and rain, provides insulation, and serves as the finished exterior of your building.

Material choice matters. The components of the thermal envelope must be durable and able to maintain their performance over decades. While a natural patina can add character, hidden degradation beneath the surface can threaten both comfort and structural integrity. Selecting materials with long lifespans—and assembling them correctly—ensures the building ages gracefully rather than deteriorates.

Moisture is the enemy of most building materials. Proper insulation placement reduces the risk of condensation, while robust flashing, weatherproofing, and a continuous air barrier protect against water intrusion. In northern climates, a smart vapour barrier on the interior helps control moisture moving through the building assembly.

Protect your home—and your health—by ensuring the thermal envelope is designed with sound building science. It’s one of the most important investments you can make in long-term resilience and comfort.

Insulation

The insulation you choose doesn’t just influence your heating bill—it directly affects indoor air quality, long-term comfort, and the environmental footprint of your home. As sustainable materials evolve, homeowners now have access to a wide range of natural, low-carbon insulation options such as cellulose, recycled denim, wool, straw bale, cork, and even mycelium-based products. Simply opting for dense-pack cellulose can dramatically reduce the embodied carbon of a project. With enough bio-based insulation, your home can even act as a carbon sink, actively storing carbon instead of emitting it—turning your building into part of the climate solution.

Investing in high-quality insulation and windows also simplifies your mechanical systems. As heating and cooling demand drops, so does the size—and cost—of the equipment required. A typical code-minimum home often consumes more than 100 kWh/m² annually for heating. When a building’s demand falls into the Passive House–aligned range of 30 to 15 kWh/m² per year, a wider array of simple, low-energy heating options becomes viable.

In smaller homes, this may be as straightforward as electric baseboards, even with higher electrical rates. For those seeking the lowest operational energy use, air-to-air heat pumps with heat recovery become an efficient choice in larger or more complex buildings. Achieving these low-energy mechanical options generally requires insulation levels in the range of R-40 to R-60 throughout the building enclosure.

By choosing the right insulation and aiming for higher performance, you improve comfort, reduce carbon emissions, and create a healthier, more resilient home.

Windows and Doors

Windows and doors are the largest intentional openings in your thermal envelope—so their performance matters. High-quality units must deliver excellent air sealing, thermal resistance, and durability. For this reason, we rely on triple-glazed wood windows and doors with multiple sealing gaskets for our projects. Their airtightness, insulation value, and long lifespan make them essential for high-performance homes.

Frames play a surprisingly large role in heat loss. Up to 30% of a window’s total energy loss occurs through the frame, which is why larger windows—where glass makes up a greater proportion of the unit—are often more energy efficient. Fixed windows also tend to outperform operable ones because their frames are slimmer and have fewer moving parts that can leak over time.

Triple glazing paired with thermally broken frames and robust European hardware significantly boosts comfort and efficiency. In Passive House design, the interior surface temperature of the window must remain within 3°C of the indoor air temperature. If it drops below that threshold, convection currents create drafts and discomfort—even in an otherwise airtight home. European Passive House–certified windows consistently meet these requirements and, in many cases, are built better and priced more competitively than domestic options.

Despite their benefits, windows are still one of the most expensive ways to capture solar heat. Thoughtful placement and sizing are essential to avoid overheating, reduce energy loss, and maintain year-round comfort. Doors deserve similar attention: many of today's triple-glazed doors offer the best performance for the cost, and when a solid wood aesthetic is preferred, Passive House–rated options are available.

Strategically chosen and carefully detailed, windows and doors become assets—not liabilities—in a high-performance building.

Air Tightness

Air tightness is one of the most important factors in creating an energy-efficient, comfortable, and durable home. By controlling how air moves in and out of the building, we keep heat indoors in winter, keep unwanted heat out in summer, and drastically reduce energy loss. Because of this, air tightness strongly influences how we design our buildings and the contractors we choose to work with.

A leaky building cannot perform well—no matter how much insulation you install. When air slips through gaps in the building envelope, it bypasses the insulation entirely. This uncontrolled airflow is responsible for the vast majority of heat loss in typical homes. It also carries moisture into wall assemblies, where it can condense and eventually lead to mold, rot, and reduced structural integrity.

Air tightness is very different from breathability. A well-built home can be airtight and made from materials that allow moisture to diffuse safely—much like a Gore-Tex jacket keeps out wind and rain while still letting moisture escape. The air barrier manages most of the moisture by preventing humid air from entering the assemblies, while breathable materials allow any remaining moisture to dry out harmlessly.

When air tightness and material breathability work together, the result is a healthy, durable building that maintains comfort with minimal energy input.

Air Quality

Healthy indoor air starts with choosing the right materials. The products used to finish the interior and exterior of your home should be non-toxic and low-emitting. Natural materials—such as clay plasters can even improve indoor air quality by buffering humidity and avoiding harmful off-gassing. Think natural wood, not vinyl; breathable plasters, not synthetic coatings.

In an airtight home, controlled ventilation becomes essential. Everyday activities—cooking, showering, cleaning, even breathing—produce moisture and indoor pollutants that need a safe path to the outdoors. A high-efficiency Heat Recovery Ventilator (HRV) or Energy Recovery Ventilator (ERV) provides this fresh-air exchange while conserving energy.

These systems introduce a steady supply of clean outdoor air and transfer heat (and, in the case of ERVs, moisture) from the outgoing stale air to the incoming fresh air. The result is a continuous flow of filtered, tempered air delivered to the main living spaces—keeping your home comfortable, healthy, and well-ventilated all year round.

Thermal Mass

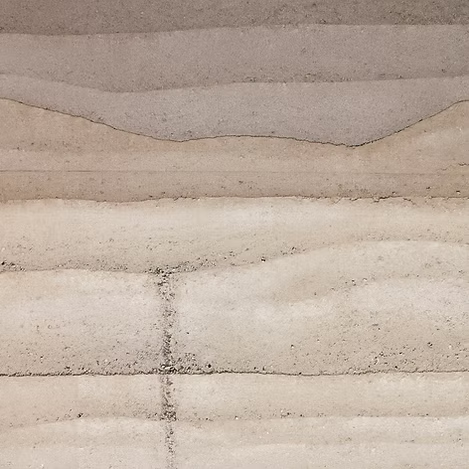

Thermal mass is the ability of heavy materials—such as rammed earth, masonry, and dense natural plasters—to absorb, store, and slowly release heat. Think of walking across a sidewalk on a warm summer evening: the ground still radiates heat long after the sun has set. Good building design can harness that same effect to keep a home comfortable with minimal mechanical heating or cooling.

In climates with significant day–night temperature swings, or in buildings strongly connected to the ground, thermal mass becomes especially effective. These high-mass materials naturally moderate both temperature and humidity. Because heavy mass tends to maintain a stable internal condition, it absorbs excess heat and moisture from the indoor air and redistributes them slowly until the wall reaches equilibrium.

As outdoor conditions change—day to night, or season to season—the direction of heat and moisture movement reverses, allowing thermal mass to continuously balance interior conditions. When insulation is placed at the center of a mass wall, it separates the indoor mass from the exterior, reducing temperature differences and slowing heat transfer. This creates the thermal lag effect: warmth absorbed earlier in the day is released hours later, just when the outdoor temperature drops.

Research shows that thermal mass used strategically can achieve comfort levels that rival homes with much higher insulation alone. Homes with significant mass often feel warmer and slightly more humid in winter, and cooler and drier in summer—naturally regulating conditions without constant mechanical intervention.

At its core, thermal mass is passive technology. It requires nothing more than the presence—or absence—of the sun.

Reductions in utility use

How we supply electricity and water in our homes—and how we use them day to day—has a major impact on overall performance. Modern mechanical systems such as heat pumps, HRVs/ERVs, and high-efficiency appliances make it possible to do more with less, but building occupants still play the largest role. In fact, more than 30% of a home’s total energy use is determined entirely by user habits, placing practical limits on how much architects and engineers can reduce a building’s consumption through design alone.

Thoughtful lighting design is a simple way to reduce energy use without sacrificing quality. Combining efficient LED fixtures with layered lighting—ambient, task, and accent—provides flexibility, comfort, and minimal electricity demand.

Appliance selection should reflect both efficiency and lifestyle. For example, in our own home, we use a chest freezer alongside a refrigerator without a freezer compartment. This configuration maximizes storage, reduces energy use, and supports our preference for buying high-quality ingredients in bulk. Someone who shops more frequently for fresh food may choose a different setup. The key is matching equipment to actual habits.

Water use follows the same principle. Low-flow fixtures are common, but performance and comfort vary by user. A low-flow showerhead may work well for some, while others find longer showers negate the water savings. Hot water systems also involve trade-offs: tankless heaters provide endless hot water but can stress energy infrastructure during peak demand, while storage tanks smooth out those peaks but use more standby energy. Each has an appropriate role depending on household needs and local conditions. High-quality low-flush toilets are available—though not all perform equally—and composting toilets offer a deeper level of sustainability for those ready to take that step.

Simple strategies like collecting roof water for gardens can reduce potable water use. Using rainwater for toilet flushing is also feasible, though it typically requires additional filtration, storage, and permitting. Fully treating rainwater for drinking is more complex in urban settings—yet, as many cottage owners know, using non-municipal water sources has long been possible with the right systems.

Ultimately, a home’s water and energy performance is a combination of smart mechanical design and mindful daily use. When both align, the results are efficient, resilient, and tailored to the way people actually live.

Thinking About Your Project?

If long-term performance, comfort, and environmental responsibility matter, a conversation early in the process makes all the difference.